What happens when a leader likens himself to one of history’s darkest figures?

The toll of blind trust and the echo of atrocities come crashing down. As the International Criminal Court (ICC) prepares to unveil the truth behind former President Rodrigo Duterte’s “war on drugs,” haunting parallels emerge between the reckoning faced by post-war Germany and the Filipino nation’s awakening.

Are we ready to confront the scars of our collective choices?

On September 30, 2016, then-President Rodrigo Duterte made a chilling statement that grabbed the headlines - likening himself to Adolf Hitler.

History records the cost of Hitler’s purges against “undesirables” at 11 million lives, 6 million of whom were Jews. Duterte’s remarks drew immediate global condemnation. World Jewish Congress President Ronald Lauder called the statement “revolting,” adding, “Drug abuse is a serious issue. But what President Duterte said is not only profoundly inhumane, but it demonstrates an appalling disrespect for human life.”

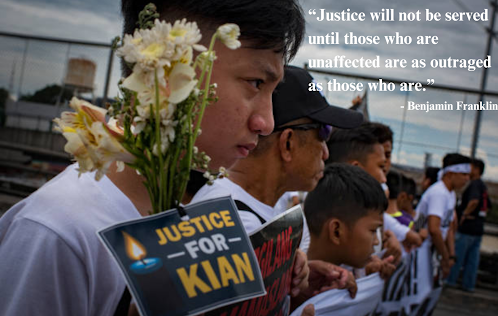

Nearly a decade later, the wounds of Duterte’s rhetoric remain fresh. VP Sara Duterte’s recent comparison of her father to Ninoy Aquino reignited public outrage, amplifying the shadow of Duterte’s likeness to Hitler. This controversy coincides with Duterte arrest by the ICC and his detention at The Hague, where he awaits trial for crimes against humanity. The parallels between Duterte regime and Nazi Germany under Hitler are now more striking than ever, as the world prepares to witness the ICC trial beginning September 23, 2025.

Unveiling Atrocities: The Holocaust and the ICC Evidence

The German people’s confrontation with the Holocaust bears a haunting resemblance to the Filipinos’ reckoning with the evidence of extrajudicial killings (EJK) under Duterte administration. Both involve societies forced to face the atrocities committed under regimes they may have supported or tolerated, leading to profound emotional and societal consequences.

The Parallel

Denial and Ignorance: Many Germans claimed ignorance of the Holocaust’s full extent, just as many Filipinos may have been unaware of the scale of EJK during Duterte’s “war on drugs.” The ICC’s presentation of evidence, including testimonies and documentation of systematic killings, forces a confrontation with this grim reality.

Betrayal of Trust: Hitler promised national revival, while Duterte vowed to eradicate crime and drugs. In both cases, the truth about the human cost of these promises leaves citizens feeling betrayed and complicit.

Emotional Aftermath: For Germans, it was the shame and guilt of realizing their complicity in genocide. For Filipinos, it is the grief of losing loved ones and the guilt of having supported policies that led to widespread violence.

Societal Reckoning: Germany underwent denazification and memorialization of Holocaust victims. In the Philippines, the ICC proceedings and the testimonies of victims’ families may catalyze accountability and healing.

Buchenwald Concentration Camp Quezon City Jail

A Hypothetical Narrative

Imagine a Filipino mother, Maria, who initially supported Duterte’s "war on drugs," believing it would make her community safer. Now, she sits in a courtroom, listening to the ICC present evidence of her son’s death as part of EJK’s systematic campaign. “I thought he was protecting us,” she whispers, tears streaming down her face. “But he took my son. How could I have been so blind?”

This moment mirrors the experiences of Germans who toured concentration camps after the war, grappling with the realization that their trust and hopes had been manipulated to justify atrocities.

The Nuremberg Trials and the Duterte Trial

The Nuremberg Trials forced Germans to confront the full scope of their regime’s crimes unveiling truths about war atrocities and the Holocaust that many had chosen to ignore or deny. Similarly, the ICC trial for Duterte could serve as a stark reckoning for Filipinos, exposing the depth of EJK. Both trials demand accountability and force societies to reconcile with their role – whether passive or active – in enabling such regimes.

The Parallel

Revealing Hidden Atrocities: Nuremberg unmasked the systematic planning of genocide and war crimes, the Duterte trial could similarly unveil the orchestration of EJK under the guise of eradicating drugs.

Moral Reckoning: Both trials create moral confrontations compelling citizens to face uncomfortable truths about their support or silence in the face of state-sponsored violence.

Erosion of Trust: Both trials betray the trust that people placed in their leaders, leaving a sense of collective guilt and sorrow.

Nuremberg Judges Duterte at ICC Pre-Trial

A Hypothetical Narrative

“I supported him,” Jose mutters, sitting in the packed courtroom, his voice cracking. “He said he would save us from drugs. I believed him. We all did.”

The prosecutor plays a harrowing video – a mother weeping over her teenage son, a victim of a vigilante killing. Jose’s hands cover his face. “I didn’t know,” he says, shaking his head. “I didn’t know it was this…” He stops himself. The truth is unbearable: he didn’t want to know.

Generational Guilt: Germany and the Philippines

In Germany, generational guilt emerged as younger citizens began questioning their families’ roles during the Nazi era, sparking intergenerational dialogues about complicity and accountability. In the Philippines, similar dynamics could unfold as younger Filipinos reckon with their parents’ or grandparents’ support for Duterte’s policies and confront the nation’s violent past.

The Parallel

Inheriting Trauma and Responsibility: Germans grappled with the weight of their nation’s history, just as younger Filipinos might feel compelled to address the human rights abuses of the “war on drugs” era.

Intergenerational Conflict: Conversations within families, where older generations defend Duterte’s policies as “necessary,” might mirror the tensions in post-war Germany, where parents justified their compliance with Nazi policies.

Cultural Reconciliation: Both societies must navigate how to remember these dark periods – whether through education, memorialization, or activism – to heal and move forward.

Drancy Transit Camp Youth street protest in Manila

A Hypothetical Narrative

“Papa, how could you have voted for him?” Liway’s voice trembles as she stares across the dinner table. “You knew people were dying. They were being killed in the streets.”

Her father sighs deeply avoiding her gaze. “We were scared, anak. Drugs were destroying lives. He promised to fix it.”

“At what cost?” she presses, her eyes welling with tears. “Our neighbor lost her son. They called him a drug addict; but he wasn’t! I know because he was my friend. And you just… watched.”

“I didn’t know, anak,” he mutters, his voice heavy with regret.

“You didn’t want to know,” she whispers, standing up and walking away, leaving him alone with his thoughts – and his guilt.

History teaches us that even in the face of enduring darkness, the pursuit of justice remains unyielding. Though truth may be delayed, it inevitably emerges, compelling nations to confront their past and hold those accountable for their actions.

As the timeless assertion reminds us: “The arc of the moral universe is long, but it bends towards justice.” This steadfast belief in hope and the transformative power of action paves the path toward compassionate healing for the Filipino people and a more just and unified future for our nation.

To our former president, Happy 80th Birthday! Wishing you peace of mind, good health, and wisdom for the years ahead.

La Salle Academy Iligan

Content and editing put together in collaboration with Bing Microsoft AI-powered Co-pilot

Head collage photos courtesy of Getty Images, ICC, Adobe Stock, & Canva

Still photos courtesy of New York Post, Eisenhower Library, Getty Images, The Guardian, & La Salle